In conversation with Brandon Tseng, co-founder and president of Shield AI

Mass force has always been a defining principle of warfare. But what happens when mass is no longer limited by the number of available pilots? Advances in autonomy are allowing militaries to confront challenges like pilot shortages and increasingly contested environments. Swarms of intelligent, collaborative systems are moving from concept to reality, promising new levels of operational scale and greater safety for the warfighters who carry out those missions in the most dangerous environments.

At the center of this transformation is Brandon Tseng, co-founder and president of Shield AI. Drawing on his experience as a Navy SEAL, Tseng launched the company in 2015 with a singular mission: protect service members and civilians with AI-powered autonomy. Today, Shield AI is pioneering technology that can fly and fight in denied environments, scale from single aircraft to swarms, and—through its partnership with Booz Allen—help the U.S. field the intelligent mass needed to compete with peer adversaries.

In this conversation with Dr. Randy Yamada, Ph.D., Booz Allen’s vice president for autonomy, Tseng discusses the origins of Shield AI, the bold decisions that shaped its growth, and the future of AI-powered warfighting.

Speed Read

Autonomous technologies from companies like Shield AI are revolutionizing warfare, enabling unmanned systems to operate in GPS- and communications-denied environments, increasing operational scale and enhancing warfighter safety.

Shield AI's rapid expansion to over a thousand employees underscores the impact of bold decisions, such as acquiring Martin UAV and Heron Systems, which accelerated its capabilities and growth in the defense tech industry.

Successful deployment of autonomous systems requires building trust through hands-on collaboration with military personnel, ensuring these technologies meet operational needs and proving their effectiveness in contested environments like Ukraine.

You co-founded Shield AI to protect service members and civilians with artificially intelligent systems. Tell us more about what problem these systems solve for the warfighter.

Since our founding in 2015, that has been our mission, and it comes from my time in the U.S. Navy SEAL teams. On deployments from Afghanistan to the Pacific to the Persian Gulf, I saw firsthand the need for this capability. At Shield AI, we are building the world's best AI pilot. The easiest way to think about an AI pilot is self-driving technology. In a military context, it enables unmanned systems to operate without GPS, without communications, and without a remote pilot. It also unlocks the concept of “teaming” or “swarming,” which, with mass being a fundamental concept of warfare, introduces the warfighting concept of unlimited mass.

Was there a defining moment when you realized that scaling this software wouldn’t just improve individual missions but could fundamentally transform the way wars are engaged?

The first problem I wanted to solve was close-quarters combat. As a Navy SEAL, that’s one of the most dangerous missions we conducted: going room to room inside buildings. It looks exciting on TV, but in reality, there’s nothing more terrifying than being in a gunfight in such tight spaces. I began talking to people about putting self-driving technology onto a quadcopter to help with those missions.

One of those conversations was with a Naval Academy classmate of mine—a mechanical engineer and F-18 pilot. He told me that the problem I was trying to solve with quadcopters indoors was the same one they were facing in the air warfare community. When you fly a drone into a building, you lose GPS and communications. At that time, during operations in Syria, our forces were beginning to experience the same thing on a larger scale: jamming that disabled GPS and communications, grounding Predators and Reapers.

He explained that fighter pilots were now facing another threat: proliferated, integrated air defense systems. Against those systems, survivability rates were extremely low. You don’t send pilots into those areas because they simply won’t come back. He told me the odds of survival were similar to stepping on an IED.

“That was my “aha” moment: realizing that the autonomy we were developing for small quadcopters could also solve a life-or-death problem for advanced aircraft in contested environments.”

Building a company like Shield AI is no small task, and timing, technology, and opportunity all play a role. Looking back, what helped you take Shield AI from an early-stage startup to a company with more than 1,000 employees today? And what advice would you offer entrants trying to cross that so-called Valley of Death between prototype and program of record?

I’d break it into two parts. First, get ready for the pain train. Building a company is full of suffering, sleepless nights, and stress in every direction. I often tell veterans who start companies that one advantage they bring is knowing how to endure hardship and still accomplish the mission. That mindset helps.

Second, you have to be bold. Every entrepreneur will face moments when the right decision feels uncomfortable or even terrifying. At Shield AI, we’ve had to make several of those “bet the house” calls, and they’ve been critical to our growth. The reality is, if you’re not making bold decisions and taking big risks, you’re not really growing.

And what would you say was Shield AI’s boldest bet?

Without question, it was acquiring Martin UAV and Heron Systems at the same time in 2021. That was an incredibly uncomfortable decision. My brother [Ryan Tseng] and I had talked about “climbing the aviation food chain,” but I always assumed we’d do it organically. At the Series C stage, you didn’t see many venture-backed startups making acquisitions of that scale.

We ultimately convinced the board that to have the impact we wanted, we had to grow inorganically. Looking back, had we not made those two acquisitions, Shield AI’s story in 2021 would have been very different—and much less positive. Within three months, we had raised $225 million and closed both deals. I’ll never forget one of our board members saying, “Holy crap, I can’t believe what just happened.” Those acquisitions gave Shield AI the platform to continue growing into what it is today.

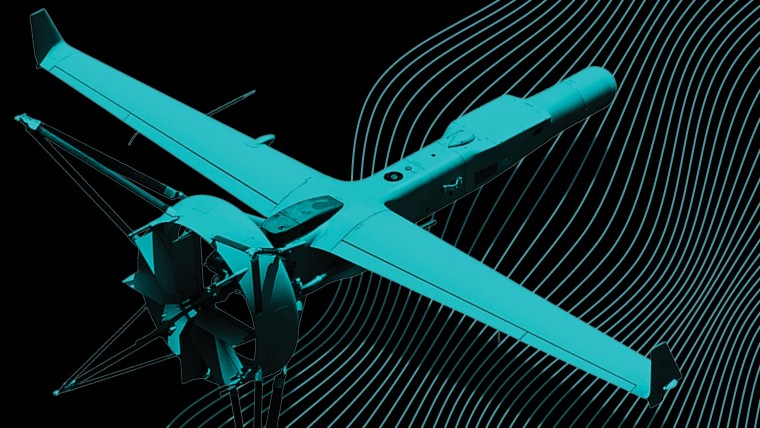

The Shield AI V-Bat is a vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) unmanned aerial system (UAS) developed by Shield AI.

The Shield AI V-Bat is a vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) unmanned aerial system (UAS) developed by Shield AI.

Another large part of that bold growth story is the V-BAT UAS (unmanned aircraft system), powered by Hivemind, which has been part of Shield AI’s portfolio for several years. What set it apart years ago and what continues to differentiate it today?

Two things set V-BAT apart. First is the hardware architecture. Its design creates a uniquely small logistics footprint and makes it easy to operate and transport. Features like the ducted fan give it advantages such as a payload-to-weight ratio roughly twice that of other vertical takeoff and landing aircraft. In practice, that means V-BAT can carry the same payload while being half the size and weight, making it a much more agile and versatile platform.

The second differentiator is software. Our autonomy is what truly makes V-BAT stand out. We’ve repeatedly demonstrated operations in GPS- and communications-denied environments, proving mission autonomy on the platform. We’ve also shown multi-agent mission autonomy, and we continue to expand those capabilities. Increasingly, software is becoming the defining factor for unmanned systems. Hardware innovation is valuable, but it’s hard to sustain differentiation there. Autonomy and mission software create a far greater competitive edge.

A good comparison is Tesla: The company disrupted hardware by committing to electric vehicles, but its real long-term advantage is in software. If you can differentiate on both hardware and software, the effect is powerful. That’s how we think about V-BAT today.

Lightning Round

One myth about autonomy you wish the Pentagon would retire this year.

That autonomy is easy. It’s not. I’d put it on par with landing a rocket from outer space in terms of technical difficulty. It takes massive expertise, resourcing, and capital to get it right—and very few companies can actually deliver.

One acquisition rule you would change tomorrow and the impact it would have on time to field.

I’d move from a requirements-based system to a problem-based one. Too often, novel solutions die in the “valley of death” simply because no requirement was written for them. If you start with the problem—say, persistent ISR over a 100-mile area—and let companies bring different solutions to the table, you’ll get faster, more innovative outcomes.

Finish this sentence: “Three years from now, autonomy will be judged successful if it has ________.”

Three years from now, autonomy will be judged successful if it has proliferated at scale because it has proven it can reliably achieve mission objectives on the toughest, most contested operational battlefields.

Adoption is always a challenge for emerging defense technologies. What has it been like to see V-BAT move from demonstration into a program of record, and how have you watched it change the way missions are executed?

It can be a painful journey. You start with innovators in the Department of War (DOW) who see the potential and are willing to prove it in the field, but those early efforts don’t always translate into scale because of the way the acquisition system works.

What really changed the conversation was Ukraine. The conflict revealed just how devastating electronic warfare can be for legacy systems—thousands of drones lost each month, and even advanced platforms like HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System) seeing dramatically reduced effectiveness in jammed environments. When V-BAT showed that it could operate for 10-plus hours, fly hundreds of miles into denied territory, and still deliver mission effectiveness, it created a global recognition that operations could be conducted differently.

That lesson is resonating in the U.S. After seeing expensive unmanned systems shot down by cheap missiles, the Army is rethinking its reliance on large, runway-dependent aircraft. V-BAT’s small logistics footprint and distributed deployment model offer a fundamentally different way to execute ISR and targeting missions. It’s helping customers reimagine how to solve problems in contested environments, moving from a requirements-driven acquisition mindset to one that starts with the operational problem and works backward.

Building adoption is one piece, but building trust is another. Beyond demonstrations and marketing, how do you ensure users have confidence in the system?

Trust doesn’t come from a single demo. It comes from working hand in hand with users as they adopt and scale the system. At the end of the day, the question isn’t “does the product work?” It’s “is the customer achieving the outcomes they need?” That requires a lot more than delivering hardware or software—it means standing alongside them to make sure they’re successful.

That’s why we forward-deploy engineers, operators, and flight personnel. When our teams are embedded with users—whether in Ukraine or with U.S. partners—they’re right next to the problem, helping solve it in real time. It shows we’re in the trenches with them, adapting the technology to the mission, and ensuring it delivers results. That proximity builds trust.

Speed is also everything in today’s environment, whether we’re talking about technology competition or mission outcomes. I’d like to talk about your vision for an “autonomy factory.” When you look at the market, there hasn’t really been a professional-grade autonomy stack—it’s been mostly open source and community-driven. What pushed you to invest in Hivemind as a product?

Shield AI participates in DOW’s recent T-REX 25-2 exercise assessing multi-agent autonomous teaming for UAVs and UGVs.

Shield AI participates in DOW’s recent T-REX 25-2 exercise assessing multi-agent autonomous teaming for UAVs and UGVs.

Strategically, we believed we had built the world’s best AI pilot. Shield AI was the first company to put an AI pilot on an unmanned system and deploy it on the battlefield—starting with a quadcopter in Afghanistan in 2018. We were also the first to execute denied-environment operations with V-BAT and to demonstrate long-endurance ISR and targeting in Ukraine. More recently, we were finalists for the Collier Trophy after flying an F-16 autonomously.

So, the question became: How do we proliferate this capability? How do we put a million AI pilots in the hands of customers in the next 10 years, and 100 million in the next 20? We realized Shield AI couldn’t do that alone. To scale, we had to enable the broader defense industrial base with the same developer tools, infrastructure, and pipelines we use internally to build autonomy. That’s what led to Hivemind Enterprise.

I want to pivot for a moment to something we’re hearing a lot about at the Pentagon: “commercial first.” As a former SEAL, what does that concept mean to you?

To me, it reflects a recognition that more R&D is happening in the commercial sector than in the defense sector. The idea is to lean on commercial solutions that already exist or can be built rapidly, rather than standing up major development programs that take years to deliver. That’s not to say large strategic systems like fighter jets or submarines won’t require government investment. But for the vast majority of capabilities, commercial products are available—or can be quickly adapted—and we should bias toward those.

I often tell program officers: I’d rather you buy a product and let Shield AI invest our own R&D to adapt it, rather than fund us directly. When the government puts development dollars into a program, it tends to move ten times slower than what a company can do with its own dollars.

And when you were in uniform, did you already think that way? Would you rather buy something that wasn’t perfect and figure out how to use it than wait three years for a requirements-driven solution?

Absolutely. As a SEAL, I was fortunate to work with an incredible range of aviation assets, from Predators to C-130s to attack helicopters. I rarely felt like I lacked capability. But whenever there was a gap, the mentality was never, “Let’s spin up the acquisition system and wait.” It was always, “What can we buy now to solve the problem in front of us?” That urgency has stuck with me.

Before we wrap up, I want to touch on Shield AI’s partnership with Booz Allen. From your perspective, how has that collaboration accelerated the mission?

It’s been fantastic working with Booz Allen. Randy, you’ve been a great partner and champion of what autonomy can mean for the world, and our visions are very much aligned.

One of the biggest realities we face is scale. Ukraine has openly talked about building a million-drone army. China will do the same. Inevitably, the U.S. will have to field its own force of millions of autonomous systems. But you can’t train enough human pilots to operate them. Even with today’s limited fleet, there’s already a pilot shortage. To unlock the power of intelligent mass, autonomy is the critical enabling technology.

That’s where the partnership with Booz Allen matters. You bring deep engineering expertise, a clear-eyed view of the technical challenges, and an ability to integrate solutions across the defense enterprise. Together, we’re building the pathways to scale it across the DOW. That’s the journey ahead, and Booz Allen has been a fantastic partner in making it real.

Shield AI tests BQM-177A drones with Hivemind AI in advanced autonomous maneuvers.

Shield AI tests BQM-177A drones with Hivemind AI in advanced autonomous maneuvers.